Tan Zi Hao, born 1989, is an artist, educator, and researcher. With years of work enveloping themes of ecological issues, political commentary, and multiculturalism, Zi Hao has become a prominent name to watch in the regional art scene, as well as one of the Malaysians featured at S.E.A. Focus 2024 in Singapore, returning for its 6th edition.

Zi Hao spoke to us recently about his inspirations behind his work for the S.E.A. Focus showcase, as well as his previous works – their recurring themes, and the motivations behind them.

For the S.E.A. Focus 2024 theme of Serial and Massively Parallel, Zi Hao told us how he came to create these new bodies of work – pieces surrounding casebearers, also known as ‘plaster bagworms’, these often overlooked insects. We rarely see them appear or move, only ever still in a bathroom corner, until they transform into moths and disappear from our sight. These casebearers thrive in humid environments, particularly in tropical countries such as Malaysia and Singapore.

Zi Hao has been creating bodies of work surrounding casebearers for several years now, telling us that the intention behind them is to incite in audiences a new appreciation towards these little ‘domestic pests’, that rarely anyone gives a second glance. The care and attention that Zi Hao extends to these casebearers – which he describes as “one of the most fundamental non-human life forms that exist in domestic spaces” – reflects his deep ecological concerns, another recurring theme in his work across his recent years as an artist.

For S.E.A. Focus 2024, Zi Hao has enlarged macro-photographs of several casebearers, from their actual size of 1 centimetre each, to around 2 metres tall each. These mega-casebearers are then suspended midair from the gallery ceiling, drawing audiences to look upwards to admire them.

Zi Hao describes these casebearers as presenting a parallel universe, in which a part of ourselves – discards from our bodies and our homes – are woven into their cases, their homes. His photographing and enlarging of these casebearers allows us to witness the detail that goes into the weaving of their cases, and how they exist in one place, in hundreds of things

Zi Hao has created various bodies of work across the last few years centering casebearers, but his other recent work appears to be vastly different – projects and installations that explore wordplay through Chinese characters.

He shared about projects such as One of You Has Expired (2023), With You (2023), and You Again (2022) – where he learned to deconstruct and reconstruct both ancient and modern scripts, to tell stories through Chinese characters.

Zi Hao told us that even though his works with casebearers appear rather different in nature from his works with Chinese characters, they explore a unified idea of things that are singular, and also plural.

He finds this to be a particularly powerful idea – that if we can begin to understand that we as humans have never been individuals, maybe we can also appreciate how things that may be essentially perceived as singular, are actually multiple in essence. Zi Hao sees this reflected everywhere; in biological life forms, and in the languages that we’re using.

To me, language is something that is singular and plural. We speak a certain language, but a language is always constituted by loan words. For example, there are many English loan words in Malay, there are many Malay loan words in Hokkien. We talk about how a language should be authentic or pure, but the evolution of a language always develops out of impurities.

The ultimate topic that I wanted to explore is questioning the idea of how we are all singular and plural at the same time. Whether that can be language, or that can be the casebearers.

So similarly when I was looking at these Chinese characters, they are actually ancient script, but they are rendered in a rather modern form. These are called the Oracle Bone Scripts or the Seal Scripts. So these are scripts that are actually written not using brush, but they are carved onto turtle shells. They have a certain kind of talismanic purpose, for shaman activities.

Zi Hao told us about his main inspiration for these projects – calligrapher Tsui Ta Tee, b. 1903, whose work we can still find traces of in signage across Penang today. Zi Hao continues to use Ta Tee’s techniques of combining old and new, to both explore characters more vividly, and to peer into our history with a tone of questioning.

We often see history as something that has a certain kind of authority or legitimacy. And I think that has been partly how history is used and abused, especially in Malaysia, or throughout Southeast Asia.

So most of my works, not only this, want to kind of question that – who writes history? Who gets to determine the official narrative or course of history? Which are the invented traditions?

The experimentation between ancient scripts and modern scripts led us to question if Zi Hao faces the same dilemma other artists do – how do I innovate? How do I go where no one else has gone? We wanted to know how he approaches looking into such traditional subject matters, each with its own extensive history, and then also trying to bring innovation into the creative process.

Zi Hao explained that his innovation arises from his limitations – that the innovative technologies he has experimented with, did not always begin as intentional choices or decisions. The root of the project is the idea, and from there the materials and process come into view, explained Zi Hao.

Similarly, when asked more about technology, and its impact on the creation and consumption of his art, he told us he views it in the same light as innovation – something that isn’t expanded on intentionally. However, he does have a deep fascination for the idea of ‘technology’ itself, telling us that he sees it etymologically, with the origins of the word technology being the idea of ‘technique’.

Technology is essentially about the way in which humans try to reveal the world. If you look at the casebearers, they have a certain kind of technology that we usually don’t see as such – how they weave different materials together, how they put them in, how they select materials, what kind of ingredients are suitable to create and construct their cases. They secrete silk filaments with which will then sync together all these harder materials that are encasing the outside. So to me that’s a form of technology. We should broaden the way we understand technology – as a form of technique, of revealing.

Zi Hao’s work features multiculturalism as a recurring theme of interest, constantly being revisited, re-explored, reinterpreted and re-presented, in newer and bolder ways. He mentioned that despite multiculturalism being something that is very dear to his work, it’s also something that he is very critical of, with an air of scepticism always hovering overhead.

He sees multiculturalism as an ideology, and not one that he would necessarily advocate for, because despite multiculturalism being perceived as a positive value, Zi Hao reminds us that it exists as a legacy of British colonisation.

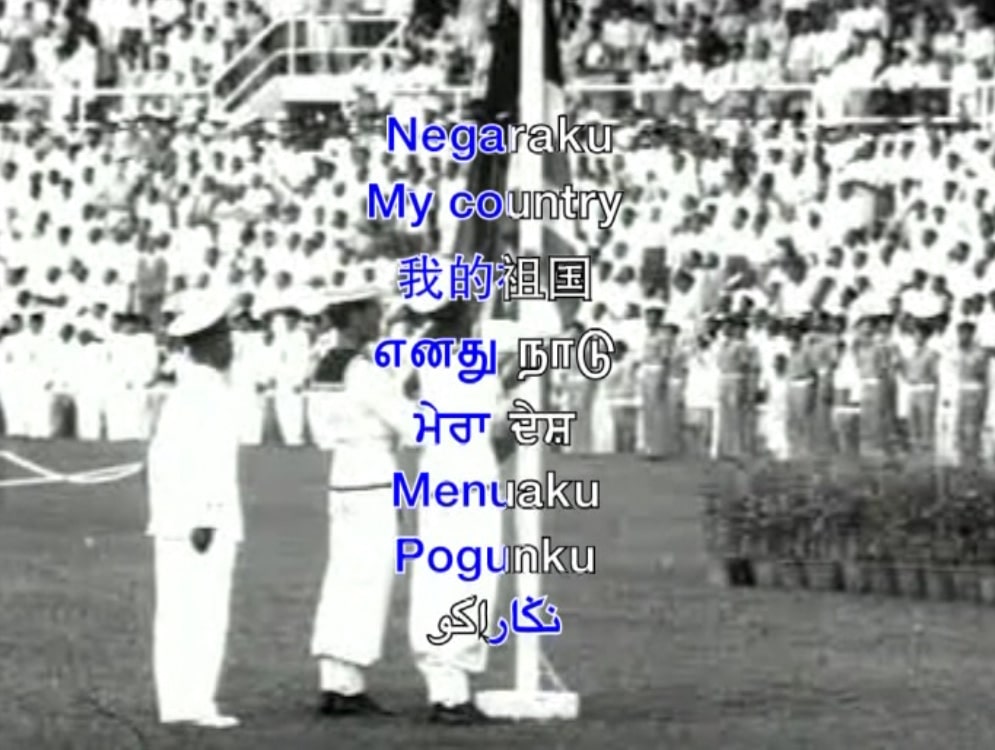

In March 2014, Zi Hao produced Negaraku. Bukan. My Country. Is Not. 我的祖国。不是。எனது நாடு. அல்ல. ਮੇਰਾ ਦੇਸ਼. ਨਾ. Menuaku. Ukai. Pogunku. Au. نڬاراکو , a single-channel video exhibited in GANGGUAN, in which he translated national anthems into a variety of languages, with the subtitles filling up the screen until the video can no longer be watched.

Translation becomes a form of smoke screen. I’m really playing with this idea that if you have the politics of recognition, if you begin to recognize every single committee’s languages, do you then recognize all, more than 100 languages throughout Malaysia? What would happen then? Because the politics of recognition is always endless.

At the same time, it’s also necessary to question what is the purpose of a national language, whether it’s for political communication or for practical reasons. I leave that up to question, but essentially I’m questioning multiculturalism itself as a form of ideology. So multilingualism is not necessarily the recognition of all languages. It is an ideology that exists in accordance with the perspective imposed since colonial times.

When asked about the Southeast Asian art market in general, and his outlook upon it, Zi Hao mentioned he’s noticed an issue with how a majority of Southeast Asian works cannot be translated into other contexts.

An example he gave us was Taring Padi – invited to Documenta Fifteen, curated by Ruangrupa from Indonesia, taking place in Germany. The distinct context that comes from where a piece is created led Zi Hao to wonder – to what extent can artwork from Southeast Asia be fully translated? Could some of these layers of complexity be explicated in other countries? And how would that be a kind of curatorial decision that has to be made for that kind of translation to happen?

We asked Zi Hao if he has concerns about this happening to him and his work – the potential of his artistic message being misinterpreted, or misunderstood. He told us that misinterpretation isn’t something that he really thinks about, since all art is bound to be viewed, understood and interpreted in a different manner – sometimes people only see what they can.

“However, the work that I do, there’s always a challenge in – how do I create something, a simple visual language, out of the kind of complexity that I wanted to articulate. So in that manner, you have to carve out the kind of the range of understanding that the audience could be exposed to. But how do they select, how do they eventually navigate with your work, it’s entirely up to them.”

Zi Hao also shared with us the unique challenges he faces as an artist creating installations with cultural or multicultural themes. The main challenge, he explained, comes from the dilemma – how do you translate an idea from something that’s complex, something you’ve extensively researched, and how do you then visualise it?

He explained that his works are configured through an extensive period of research, with a lot of exploration through reading and sketches. Eventually, the challenge becomes, how do you then visualise those layers of complexity in the form of a presentation?

“It’s just one singular moment when people encounter your work. It’s just one moment. How do you explain the extensive research that you have? How do you explain the kind of complexity that you intend to communicate using this single visual plane? That’s always a challenge.”

What makes Zi Hao’s work engaging is his ability to capture the essence of Malaysia itself – not merely through political and social commentary, but through his ability to see things as singular and plural simultaneously. In our ability to be one nation, but so infinitesimally composite at the same time, we become the embodiment of Zi Hao’s subjects, allowing us to relate to his work in our own unique way.

S.E.A. Focus returns for its 6th edition with Serial and Massively Parallel, an assemblage of regional artworks by over 40 artists from 22 galleries from Southeast Asia, curated by John Tung. Malaysian galleries featured include A+ Works of Art, Richard Koh Fine Art, and Wei-Ling Gallery. S.E.A. Focus 2024 happens January 20th to January 28th, at 39 Tanjong Pagar Distripark, Singapore.

For more information on Tan Zi Hao’s works, click here.

Written by Komal Keshran

*The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed are those of the writer